Providing Context: Review, Preview, Motivate

Most faculty know that the best practice when designing a course is leveraging the principle of backwards design: Begin with where you want your students to end (what skills and knowledge you want them to develop), and work backwards from there. From a practical standpoint, this means beginning by articulating your learning objectives, then identifying your assessments, and finally selecting your instructional materials. Your instructional materials should prepare students for the assessments, and the assessments should demonstrate your students’ achievement of your learning objectives. As we discussed in our video on course mapping, a great way to approach this process is to develop a course map, which helps to ensure (and illustrate) the alignment between all three of these essential course components.

What isn’t often discussed is the importance of establishing context. Context should be provided at every level of your course: for your course as a whole, each of its modules, and every single piece of instructional material. Students need to know how your course is important (either in the degree program in which it’s located or how the skills they’ll learn are relevant to the real world), how your modules fit together to form a larger narrative, and how each piece of instructional material is essential to accomplishing your course’s objectives. Providing context at each level of your course will help students better understand your goals, your approach, and how all of the pieces of the course relate to one another as well as to issues in the real world.

Accordingly, in this article, we’ll look at why context is so important, and think through strategies on how to create and present it.

Chunking

One best practice for course design is to chunk your instructional materials. What is a “chunk?” In this context, a chunk refers to “an organizational unit in memory,” and the act of “chunking” refers to breaking down larger pieces of information into more easily remembered—though still related—pieces (Meyer, 2005, p. 1). For example, many of us have memorized phone numbers as chunks, since a number like “(216) 555-0413” is much easier to recall than simply “2165550413.” Similarly, most of us like reading text that’s broken up into sections and paragraphs rather than a large wall of uninterrupted text.

This same principle from cognitive psychology applies to course design. The instructional materials you assign should—as much as possible—address specific objectives you want your students to achieve. In the language of our course mapping process, this usually means addressing one or possibly two micro-objectives. Your materials should contain only information that’s relevant to your objectives and worthy of assessment and shouldn’t include information irrelevant to your learning goals. In the language of cognitive load theory, you want to eliminate extraneous load.

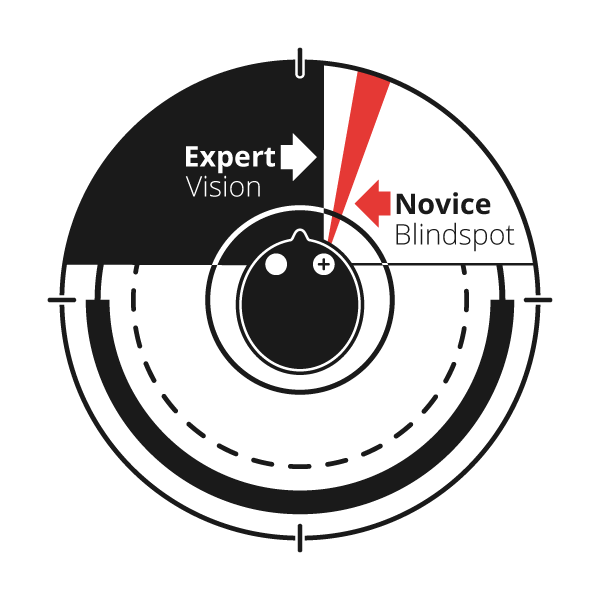

Chunking can be a side effect of creating a course map. By doing so, you help ensure that the discrete chunks of material you select are in alignment with your assessments as well as your learning objectives. The problem arises, though, that while you may understand the relationship between all of these chunks, students may not. The reason is because of a phenomenon called “expert blind spot.”

Expert Blind Spot

Expert blind spot refers to the fact that instructors, as experts, understand how skills and knowledge relate to each other, whereas students, as novices, may not. To you, everything seems so clear, and your choice of instructional materials obvious.

Expert blind spot refers to the fact that instructors, as experts, understand how skills and knowledge relate to each other, whereas students, as novices, may not. To you, everything seems so clear, and your choice of instructional materials obvious.

Try this as a thought experiment when you’re with a friend: Tap out the rhythm of the song “Three Blind Mice” on a table and ask your friend if they recognize the song you’re tapping. Chances are they’ll have no idea what song you’re playing. But it sounds so obvious to you! That’s a (simplistic) representation of expert blind spot.

There are obviously big differences between novices and experts. Experts recognize patterns and understand how they fit into a broader picture. When they encounter new information, they know where it belongs within a larger knowledge structure, and unconsciously chunk the information on their own. When they have to call upon information they’ve learned, they can do so with relative ease. Novices, on the other hand, may only see the pieces independently of any big picture, and without a meaningful framework to put them into, they may encounter difficulty understanding, chunking, or recalling.

Accordingly, expert blind spot refers to when instructors are unaware of or ignore the struggles that their students have (as novices) in incorporating new information. One way to compensate for this is to provide context for everything your students must learn.

How to Approach Providing Context

When thinking about how to present context, remember this mantra: Review, preview, motivate. Given that you should provide context at every level of your course (course, module, materials), we’ll refer to these statements as context statements.

Review

Part of your context statement should focus on how the content students are about to consume builds on what they’ve learned in previously. This is what’s referred to as activating prior knowledge. In their seminal work How Learning Works, Norman, Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, and Lovett (2010) discuss the strong role that prior knowledge can play in learning, for good or for ill. And given how effective learning is when you scaffold knowledge and skills, it’s essential that students have an accurate “scaffold” beneath them. The context statement should serve to reinforce that the existing foundation underpinning students’ learning is built to spec, as it were. Research indicates that even token efforts to activate students’ prior knowledge can have a positive effect on learning (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 16).

Part of your context statement should focus on how the content students are about to consume builds on what they’ve learned in previously. This is what’s referred to as activating prior knowledge. In their seminal work How Learning Works, Norman, Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, and Lovett (2010) discuss the strong role that prior knowledge can play in learning, for good or for ill. And given how effective learning is when you scaffold knowledge and skills, it’s essential that students have an accurate “scaffold” beneath them. The context statement should serve to reinforce that the existing foundation underpinning students’ learning is built to spec, as it were. Research indicates that even token efforts to activate students’ prior knowledge can have a positive effect on learning (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 16).

Context Statement Examples: Review

When you’re online, do ads pop up that seem tailored to your own tastes and buying habits? We’ve already seen the methods that marketers use to gather this information, but is it possible to stop them? In this module, we’ll reexamine these tactics with a more critical eye and also address …

Up to this point in the course, we’ve focused on normal adolescent development; now, let’s turn to an examination of abnormal adolescent development. In this module, we’ll be focusing on …

We looked at several works of Freud in previous modules and examined his influence within the realm of psychology and behavioral health. You may not know, however, that his work heavily influenced literary analysis and literary theory. In this module, we’ll look at back at what you’ve read already and instead explore …

Preview

Your context statement should also give students an idea of what they’re going to be consuming, the assessments they’ll complete, the activities they’ll encounter, or the learning goals they’ll accomplish. You can continue to elaborate based on whatever “reviewing” you’ve done so far of how the current content builds on their prior knowledge.

Your context statement should also give students an idea of what they’re going to be consuming, the assessments they’ll complete, the activities they’ll encounter, or the learning goals they’ll accomplish. You can continue to elaborate based on whatever “reviewing” you’ve done so far of how the current content builds on their prior knowledge.

“Previewing” should also give students guidance on how to consume the material and how it all fits together. This is one of the key strategies in addressing your expert blind spot. Learning research indicates that when students are presented some sort of organizational structure (or “advance organizer”) that contextualizes material they’re about to encounter, their understanding and recall improves (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 53).

So, ask yourself, “Are there particular arguments that link the materials together? Should they pay attention to particular pages of a reading? Are there ‘red herrings’ of which students should be aware?” Though, presumably, the order of your course components (or their due dates) will dictate a chronological order to their consumption, students should have an idea of how the course materials in the module relate to one another and what they should be on the lookout for.

Context Statement Examples: Preview

In this classic article, Clifford Geertz uses the concept of “deep play” to describe the symbolic importance of cockfighting in Balinese culture. As you read, ask yourself: What are some forms of deep play in this culture, and what do they say about us?

The learning goals for this session are for you to be able to (a) solve optimization problems using MATLAB and (b) explain the reasoning behind your problem-solving strategy.

The four essays you’ll be reading all address the topic of postwar feminism. Some of them aren’t explicit about it, though, so keep an eye out for opinions they express either directly or indirectly.

Motivate

Your context statement should also include information that explains why the material is relevant to course goals, how it relates to the real world, and how future material builds on it. Students’ motivation is heavily influenced by the value that they assign to the course and its content, and explicitly articulating that value is key to building your students’ motivation and, in turn, promoting engagement and retention.

Your context statement should also include information that explains why the material is relevant to course goals, how it relates to the real world, and how future material builds on it. Students’ motivation is heavily influenced by the value that they assign to the course and its content, and explicitly articulating that value is key to building your students’ motivation and, in turn, promoting engagement and retention.

One way to consider the “motivation” piece of your context statement is to create a hook. Begin your context statement with a demonstration of a real-world process, a discussion of common incorrect prior knowledge, a discussion of a relatively current event, or an observation of a phenomenon that relates to the upcoming material. This piques students’ interest and can enhance their motivation to consume and engage with the material more deeply.

Context Statement Example: Motivate

In 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge began to pitch and buck before collapsing into Puget Sound. In this lecture, we’ll learn how a proper understanding of eigenvalues and oscillation might have prevented this disaster …

On your final exam, you’ll be asked to apply negotiation principles to a case study in international business. In this lecture, we’ll examine two of these principles in depth …

[Video] Have you ever wondered why ice floats on water while other solids usually sink? [Performs demonstration on camera by dropping ice into a bowl of water, which floats, then small pebbles into a different bowl of water, which sinks.] Water molecules do some interesting things as they approach their freezing point. In this module, we’ll explore the unique thermodynamic properties of water, and you’ll be able to …

Conclusion

As mentioned above, context statements should occur at every level of your course: the course level, the module level, and at the level of your instructional materials. Providing context for your course as a whole can obviously occur within your syllabus, but you can also create a course introduction or even an announcement in the first week of the course. Module introductions are excellent and obvious vehicles for providing context for your modules, and making them into videos is a great way to establish presence and build community. For your context statements for your instructional materials, leverage the “description” field within your learning management system. If you’re the author of the material (or if you have permission to edit the material, such as with an open educational resource), you have an opportunity to include a context statement at the beginning of the material itself.

Providing context will help scaffold your students’ skills and knowledge and illuminate your course narrative. If you’ve chunked your material appropriately and compensated for expert blind spot, the context you provide will foster a metacognitive perspective, which will consequently help students take more ownership over their learning. While time is certainly required to provide the appropriate level of context, the effort will be well worth it.

References

Norman, M. K., Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., & Lovett, M. C. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Meyer, K. (2016). How chunking helps content processing. Retrieved from https://www.dropbox.com/s/o7ljmj1cbj6bl4r/How%20Chunking%20Helps%20Content%20Processing.pdf?dl=0